Kenichi Zenimura’s Field of Dreams

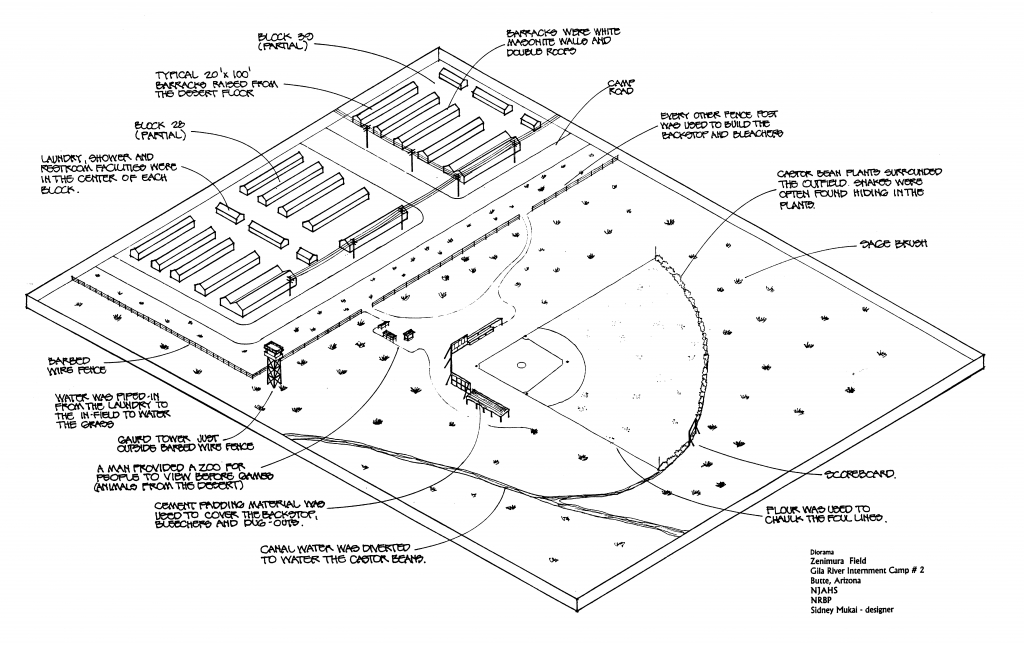

With the arrival of the internees at Gila River and Poston Camps I, II, and III in Arizona, the camps became the third and fourth largest cities in the state overnight. More than thirteen thousand internees filed into the Gila River Camp II in Butte. The camp’s buildings were designed with double roofs to help ventilate the barracks and provide some protection from the intense desert heat. The internees shredded sheets and used the strips to stuff the cracks in the floor in order to keep out the clouds of dust that would enter the rooms during the harsh wind storms. On the exterior of the housing units, reflective white sheet rock was used to reduce the searing heat.

Among the internees at Gila River were Kenichi Zenimura, his wife, Kiyoko, and their sons, Howard and Harvey. Later Kiyoko reflected on Kenichi’s anger over having been sent to Gila River instead of to Jerome, Arkansas, where his ball-playing peers were sent. “He left his suitcases packed for two weeks. He didn’t even bother opening them,” she recalled. But one day Kenichi looked out from Barrack 13C, Block 28, on the corner of the detention facility, at the vast desert surrounding the camp. For most, the sagebrush, rocks, and cactus were a vision of hopelessness and desolation. For Zenimura the scene meant the possibility of another ballpark. Kenichi had already built the Japanese ballpark on the west side of Fresno bordering the city dump in the early 1920s. The Fresno assembly center was his second diamond, and now Gila River became his crown jewel.

Among the internees at Gila River were Kenichi Zenimura, his wife, Kiyoko, and their sons, Howard and Harvey. Later Kiyoko reflected on Kenichi’s anger over having been sent to Gila River instead of to Jerome, Arkansas, where his ball-playing peers were sent. “He left his suitcases packed for two weeks. He didn’t even bother opening them,” she recalled. But one day Kenichi looked out from Barrack 13C, Block 28, on the corner of the detention facility, at the vast desert surrounding the camp. For most, the sagebrush, rocks, and cactus were a vision of hopelessness and desolation. For Zenimura the scene meant the possibility of another ballpark. Kenichi had already built the Japanese ballpark on the west side of Fresno bordering the city dump in the early 1920s. The Fresno assembly center was his second diamond, and now Gila River became his crown jewel.

Howard Zenimura was there the day the men began clearing away sagebrush from the desert floor. “Right near our block was an open space, so we started digging out the sagebrush with shovels,” Howard said many years later. “Pretty soon people came by to ask us what we were doing. We told them we were building a ballpark and then everybody was out there with their shovels clearing that space. We piled up the brush and burned it, and my dad somehow got a bulldozer to level the ground.”

Not content with simply having a cleared space to play, Zenimura and the other men liberated every second four-by-four from the barbed-wire fence surrounding the camp until they had enough to build a frame for the backstop. Then they took thick padding that was used to keep wet cement from drying too quickly and hung it over the frame to provide a cushion for errant fast balls and other wild pitches. (The only catch was having to pick up all the pads each day and check for rattlesnakes or scorpions.)

Next they worked on the mound and infield, scraping the top layer and sifting out rocks and pebbles. One of the internees who helped was James “Step” Tomooka, a hard-hitting outfielder whose Guadalupe YMBA squad would win the camp’s inaugural “A” championship. (His nickname stemmed from his foot speed, or perhaps the lack thereof.) Along with the Zenimuras, James got down on hands and knees to seek out every pebble before the internees diverted water from a nearby irrigation ditch and flooded the infield to harden and pack it down. Then they took a three-hundred-foot water line from the laundry room and made a spigot at the back end of the pitcher’s mound so that they could have Bermuda grass in the infield and outfield. A castor-bean home run fence was grown, which reached eight to ten feet in height.

After the field was laid out, the next project was a grandstand. “We needed lumber,“ said Harvey Zenimura. “We were in Block 28 and the lumber yard was way across the other side of the camp, probably another mile away. We’d go out there in the middle of the night and get lumber and lug it all the way out into the sagebrush, bury it in the desert, and then go back later and get it as we needed it. The camp officials probably knew what was going on, but nobody said anything.”

After the field was laid out, the next project was a grandstand. “We needed lumber,“ said Harvey Zenimura. “We were in Block 28 and the lumber yard was way across the other side of the camp, probably another mile away. We’d go out there in the middle of the night and get lumber and lug it all the way out into the sagebrush, bury it in the desert, and then go back later and get it as we needed it. The camp officials probably knew what was going on, but nobody said anything.”

When the stands were completed, the bleachers had four or five rows. Zenimura went so far as to provide individual box seats on the planks. “My dad marked the benches with paint,” remarked Harvey. He drew lines and put numbers in so that anybody that donated a lot of money would get his good box seat.” The park’s “box office” consisted of coffee cans at two different entrances where fans could deposit donations to watch the game. In addition, at every game a collection was taken up. Zenimura used the proceeds to have baseball equipment shipped from a Fresno sporting-goods dealer. In a 1962 interview, he claimed to have ordered about two thousand dollars’ worth of equipment from Holman’s Sporting Goods.

Actor Noriyuki “Pat” Morita, who was interned with his family at Gila River and grew up to star in The Karate Kid, among other movies, retained a vivid memory of the work that went into maintaining the diamond: “I remember watching this little old brown guy watering down the infield with this huge hose. He used to have his kids dragging the infield and throwing out all the rocks. Jeez, I was glad I wasn’t them. They worked like mules.” Keeping the field in playing condition, and ensuring that fans were as comfortable as possible, demanded constant labor. Cement-drying pads covered the dugouts and bleachers to provide shade against the desert sun, while the pebbles strained from the infield were spread below the bleachers and on the dugout floors to keep the dust down.

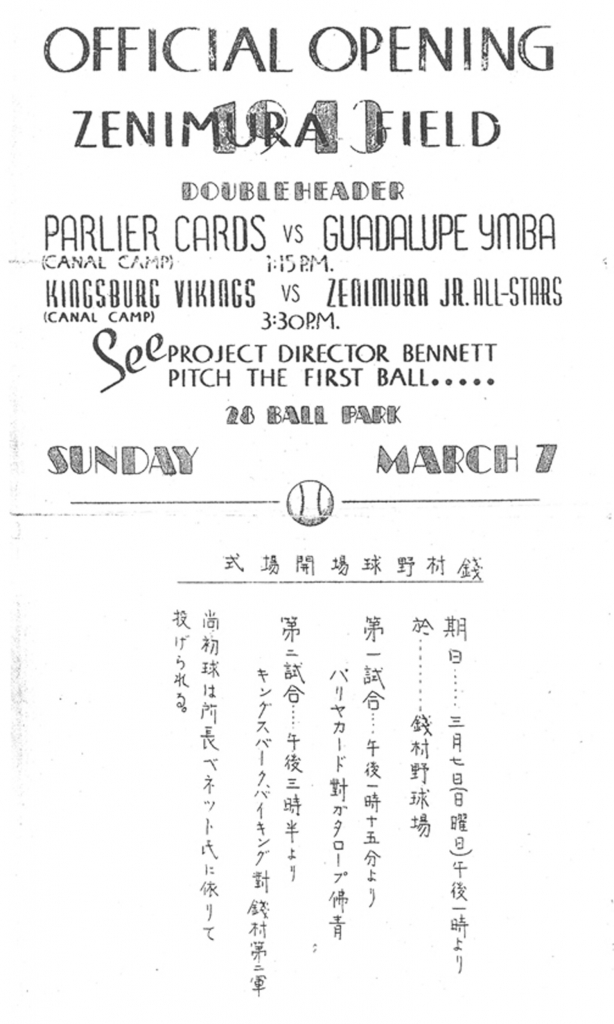

Thirty-two teams in three divisions competed at Gila River, where the climate allowed for practically year-round play. “The games were very competitive,” recalled James Tomooka. As in the other camps, playing, watching, and supporting baseball brought a sense of normalcy to very abnormal lives and created a social and positive atmosphere. As Pat Morita described it, “The teenagers and adults would gather every night to watch the games. I’d never seen a live baseball game before, so this was my introduction to baseball—sitting and cheering with a couple thousand rabid fans.” For Pat and other fans, recalling better times and longing for their return, Kenichi Zenimura’s diamond in the sagebrush was truly a field of dreams.

##